I don’t believe I’ve ever been nostalgic about political life in November 2016. It was a disorienting time for Americans and people around the world. But there’s one way we can look back at that jarring moment and see a simpler — even straightforward — time.

November 2016 was perhaps the peak — at least among a certain class of liberal-leaning people aghast at the election of Donald Trump — of a belief in the power of information to change minds and votes.

It was misinformation that did the deed, you see? Fake news! It’s all Facebook’s fault, for spreading that fake story about Pope Francis endorsing Trump. What we need is a new army of fact-checkers, stat! The truth shall set us free!

In the broader liberal hunt for explanation, this idea — that the reason that so many people voted for Trump must be that they were misinformed, that they didn’t have access to the capital-t Truth — was appealing to many. (Just like all the “economic anxiety” takes.) It avoided reckoning with the idea that darker forces — racism, sexism, and authoritarianism, to name a few — were playing a bigger part than generally acknowledged.

Today, almost seven years later, we know better. Or at least we have a more nuanced perspective on things. Yes, a lot of misinformation spread on Facebook; yes, a lot of people got a lot of their political news from dubious sources. But we know now that people’s brains don’t have an on/off switch that gets flipped by a well-made factcheck. People’s beliefs are driven by a huge number of psychological and social factors, far beyond whether they follow PolitiFact on Instagram. Knowledge alone doesn’t knock out beliefs held for deeper reasons — and sometimes, it entrenches them more deeply.1

You can see those extra layers of nuance in a lot of the academic research in the field. Like in this paper, which came out in preprint recently. It argues exactly what it says on the tin: “Partisans Are More Likely to Entrench Their Beliefs in Misinformation When Political Outgroup Members Fact-Check Claims.” Its authors are Diego A. Reinero (Princeton postdoc), Elizabeth A. Harris (Penn postdoc), Steve Rathje (NYU postdoc), Annie Duke (Penn visiting scholar), and Jay Van Bavel (NYU prof).

Here’s the abstract:

The spread of misinformation has become a global issue with potentially dire consequences. There has been debate over whether misinformation corrections (or “fact-checks”) sometimes “backfire,” causing people to become more entrenched in misinformation.While recent studies suggest that an overall “backfire effect” is uncommon, we found that fact-checks were more likely to backfire when they came from a political outgroup member across three experiments (N = 1,217).

We found that corrections reduced belief in misinformation; however, the effect of partisan congruence on belief was 5× more powerful than the effect of corrections. Moreover, corrections from political outgroup members were 52% more likely to backfire — leaving people with more entrenched beliefs in misinformation.

In sum, corrections are effective on average, but have small effects compared to partisan identity congruence, and sometimes backfire — especially if they come from a political outgroup member. This suggests that partisan identity may drive irrational belief updating.

The paper’s three experiments shared a basic format. People were shown a tweet that contained some form of misinformation, then asked to rate how much they believed it, how confident they were in their level of belief, and how much they’d be willing to share the tweet with others. Then they were shown a different tweet from a different source that fact-checked and corrected the misinformation — and then asked the same questions again about how much they believed the first tweet.

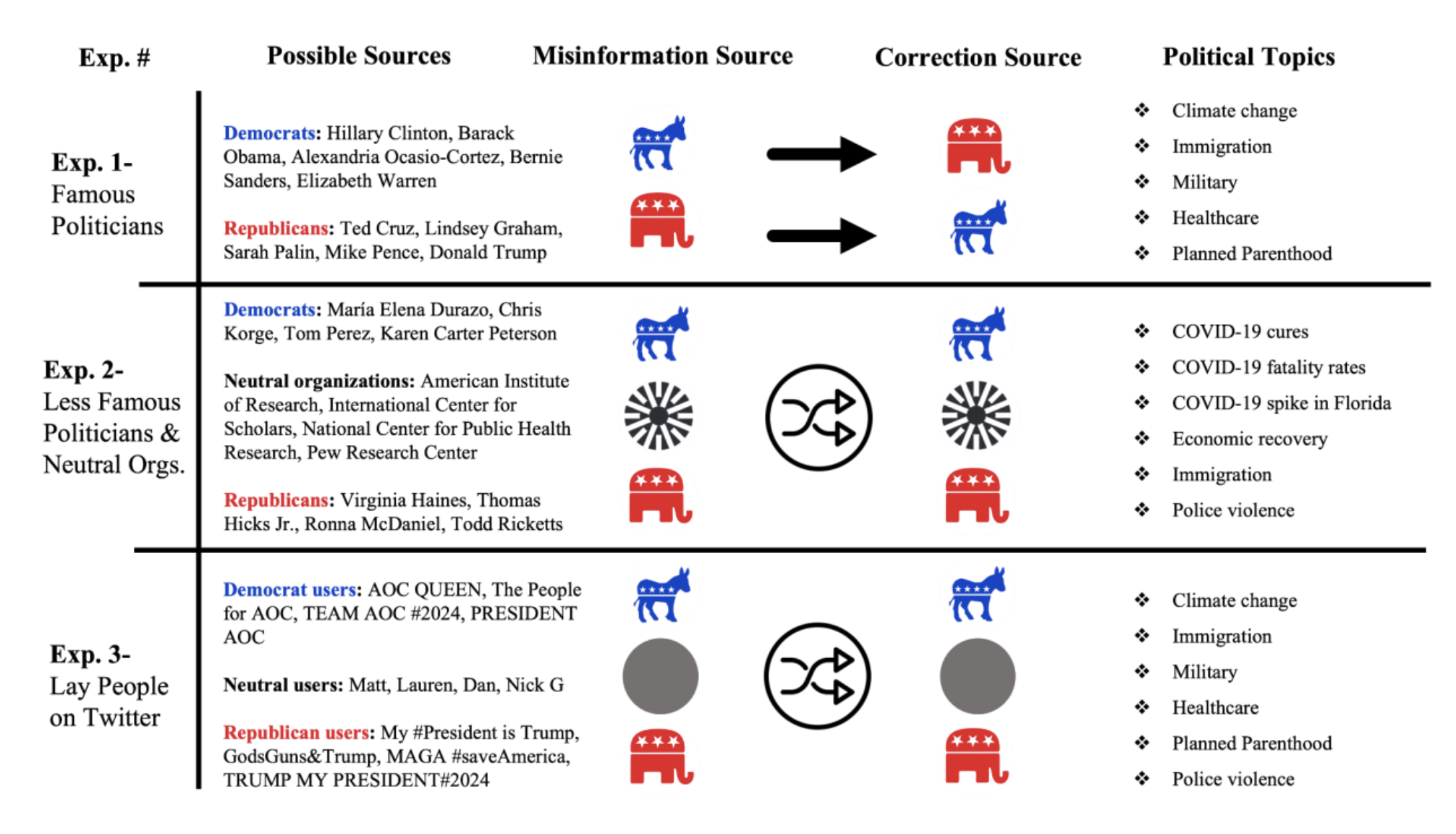

This basic format allowed experimental manipulation of the apparent sourcing of each tweet. Sometimes, a tweet was shown as coming from a very well-known politician. (We’re talking Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump, Ted Cruz, Elizabeth Warren, Sarah Palin — that level of famous.) Sometimes it was sourced to a less-known partisan figure, the sort you need to be a bit of a political junkie to recognize. (Think Tom Perez, Ronna McDaniel, Todd Ricketts, or Karen Carter Peterson.) Sometimes it was sourced to an unknown but obviously partisan Twitter user (with names like GodGuns&Trump or TEAM AOC #2024). And sometimes the tweeter was portrayed as a nonpartisan source (American Institute of Research, Pew Research Center) or a random Twitter user with no obvious signs of partisanship in their profile.

In their first experiment — the one with the big names like Obama and Trump — corrections always were shown as coming from the opposite political party. So Republicans corrected Democrats, and Democrats corrected Republicans. But in the other two, with the somewhat more obscure sources, corrections were tested in all variants — coming from a fellow partisan, a political opponent, or a neutral party.

The results showed how important the source of a factcheck is — and, often, how little effect they have at all. They also address an ongoing debate within the field about that so-called “backfire effect.” Are there times when correcting the facts for someone will lead them to double-down and believe the false information even more? (Yes, there are times, everyone seems to agree; the debate is about how rare or common occurrence it is.)

In the big-name-pols study, the authors expected to see a divided response based on partisan side. In other words, if a Bernie Sanders tweet is corrected by an Elizabeth Warren one, they’d expect Democrats to move their beliefs in the correct direction. But if that Bernie tweet is corrected by a Donald Trump one, they expected Democrats to double down and believe Bernie even more.

Instead…correcting worked both ways! But only a little bit.

While we expected that seeing an outgroup politician be corrected by an ingroup politician would successfully reduce belief in the misinformation, we thought that seeing an ingroup politician be corrected by an outgroup politician might backfire. Instead we found that corrections were successful in both conditions, albeit with very small effects.

Those small effects? The average person moved their belief only 3.7 points on a 100-point scale. So if you believed something false with a confidence rating of 77 before, you might only have 73 percent confidence after seeing the correction — a little more if it’s coming from someone in your political tribe, a little less if it’s coming from the other team.

It’s good news that the direction was positive in both cases — neither one “backfired” — but the impact is still tiny compared to good ol’ partisanship. “In fact,” they write, “these results suggest that partisan identity is roughly 12× more powerful than fact-checks in shaping belief in misinformation.”

And just because the corrections didn’t backfire on average doesn’t mean they didn’t backfire in lots of individual cases. This chart lays out the individual-level impacts across the three experiments2, and the trend is pretty consistent across them. People move their belief toward the truth about half the time after a correction; about a quarter of time, they believe the wrong information even more; and in the remaining quarter of the time, the correction has no impact at all.

But those results look very different depending on the source of the correction.

Backfiring was largely driven by partisanship. Fact-checks that came from an outgroup politician were 93% more likely to lead to a backfire. We also found that being more politically conservative was linked with a 11% higher likelihood of backfiring. In addition, male participants had a reduced likelihood of backfiring. Taken together, backfires were more likely when corrections came from outgroup politicians, when the participant was more politically conservative, and among females, with the effect size for group membership being much larger than all other variables. ((For readability, I’ve removed some stats stuff from this paragraph; you can find it all in the paper.

In other words, whether or not we believe a factcheck is, to a great degree, a function of how much we identify with the person doing the correcting. If the source is a fellow partisan, we’re a little more likely to adjust our beliefs. But if it’s coming from the other side, we’re 93% more likely to dig our heels in and back the inaccurate side.

What about if the correction source isn’t as famously associated with a political side? Lots of people have preconceived notions about Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez or Lindsey Graham; they likely don’t about RNC member Virginia Haines or DNC member Chris Korge. What if the corrections are coming from a partisan, but an unfamiliar one?

We replicated our findings from Experiment 1. Participants believed misinformation that came from ingroup politicians far more than from outgroup politicians. In addition, we found that the more participants identified with their own political party, the more they believed misinformation on average. We also found that participants believed misinformation from neutral organizations more than from outgroup politicians.Interestingly, we found that misinformation from ingroup politicians was believed more than from neutral organizations at the outset. This highlights the strength of partisanship: even well-established and trusted neutral sources (e.g., Pew Research Center) were believed less than ingroup politicians. This was true even when participants did not know the politician, as evidenced by the low recognition scores on our politician quiz. This suggests that partisan content was a powerful cue for belief.

Coming from these lesser-known sources, corrections had a bigger positive effect. They moved people’s beliefs, on average, by 9.3 points on that 100-point scale — a lot more than the 3.7 points the Obamas and Trumps provoked. And backfiring was a bit less common. But even here, partisan identity was still 3× as powerful as a factcheck in determining beliefs.

Finally, what about all the Joes and Janes on Twitter, America’s favorite home for calm, rational political discourse? How do people respond to the corrections of Twitter randos, with or without some obvious partisan flair on their profiles?

Well, it’s more of the same. People are more likely to believe corrections from their fellow partisans than from neutral parties, and corrections from neutral parties more than from the other side. The average shift on people’s beliefs after the correction was 5.9 points on the 100-point scale — bigger than the big political names, but smaller than the little-known politicos. Partisan identity was about 5× more powerful than fact-checks, between the other two.

Who were the types of people who was the most resistant to backfire? That is, the ones who were least likely to double-down on wrongness in the face of facts? Two wildly different groups: the “intellectually humble and ideologically extreme.”

The first of those makes sense: People who (based on their responses to survey questions) are less arrogant about their beliefs are less likely to stomp their feet and insist only they know the truth. But what about the “ideologically extreme”?

While seemingly counterintuitive, this small ideological extremity effect appears to be a result of an ingroup bias among ideologically extreme participants. That is, all participants sometimes backfire when an outgroup member issues the correction, but ideologically extreme participants (relative to more ideologically moderate ones) are less likely to backfire when an ingroup member issues the correction. Thus, on average, ideologically extreme participants were less likely to backfire overall. Taken together, backfires were more likely when corrections came from outgroup Twitter users and less likely among more intellectually humble and ideologically extreme participants.

In other words, the hard-core ideologues are so set in their beliefs they don’t even listen to their partisan tribe, much less the other one.

I don’t know that a lot of this paper’s findings would be considered unexpected. The strength of tribal identity in the partisan mind is an established fact of political life today. But there’s still something jarring about seeing how small the impact of correct information can be — even in those ideal cases where it’s someone from your political team doing the correcting.

While corrections were somewhat effective across sources, the effect of partisan congruence on belief was 5× as large as the effect of corrections. That is, relative to the small effect of corrections, partisans believed misinformation from political ingroup sources far more than from neutral or outgroup sources.We also found that partisans were more receptive to corrections that came from ingroup or neutral sources, relative to outgroup sources — a partisan bias in belief updating. Indeed, corrections from political outgroup members were 52% more likely to backfire (especially when the correction came from a famous politician), leaving people more entrenched in their belief in misinformation. This suggests that partisan identity may drive irrational belief updating.

These results suggest that political ingroup members can be both a risk and remedy when it comes to belief in misinformation…This suggests that social identity plays a key role in belief formation — and people are far from unbiased updaters. Although fact checks did work, suggesting that people do incorporate new information, this was a much smaller effect than the impact of partisan identity.

Moreover, the impact of partisanship was consistent across well-known and obscure political figures, indicating that this was largely an effect of partisan identification rather than trust in or familiarity with individual politicians. Taken together, this underscores the need to consider the role of identity when addressing the impact of misinformation, corrections, and identifying effective solutions in political contexts.

- I should note the obvious here: A lot of people recognized this before November 2016, too.

- The first was, as mentioned, the one with the famous politicians. No. 2 involved the lesser-known politicians and neutral sources, and No. 2 used the obviously partisan and seemingly rando Twitter users.